In yet another inspirational reminder that the world’s largest military can still misplace things, a Nigerian village in Yobe State found itself on the receiving end of a US strike that locals insist has nothing to do with ISIS, terrorism, or anything more radical than arguing over football scores. The incident, first reported by Egypt Independent under the headline “Fear and confusion in Nigerian village hit in US strike, as locals say no history of ISIS in area” (Dec 2025), has now migrated from the foreign news section to the crowded waiting room of global political disasters.

The strike, reportedly carried out under the ever-expanding mandate of US counterterrorism operations in Africa, targeted a remote village whose most dangerous known activity to date appears to be the overuse of WhatsApp voice notes. Residents of the Nigerian community say the only cells they have are on their mobile networks, not in clandestine terrorist franchises.

“We have no ISIS here, we barely have electricity,” said one local elder, looking understandably confused that the world’s most expensive weapons platform had just RSVP’d to a village that doesn’t even show up properly on Google Maps. “If ISIS was here, do you think our generator would still sound like this?” he added, as the machine delivered the audible equivalent of a dying goat.

At the Pentagon, officials offered the familiar holy trinity of modern foreign policy responses: regret, ‘ongoing investigation,’ and a suspicious amount of PowerPoint.

“Based on initial assessments, the strike was conducted against what we believed to be ISIS-affiliated militants operating in Yobe,” said a Pentagon spokesperson, speaking from a podium decorated with an American flag and absolutely no irony. “If subsequent information suggests otherwise, we will take that information very seriously, as we always do, right before filing it in the large, overflowing cabinet marked ‘Complex Situations.’”

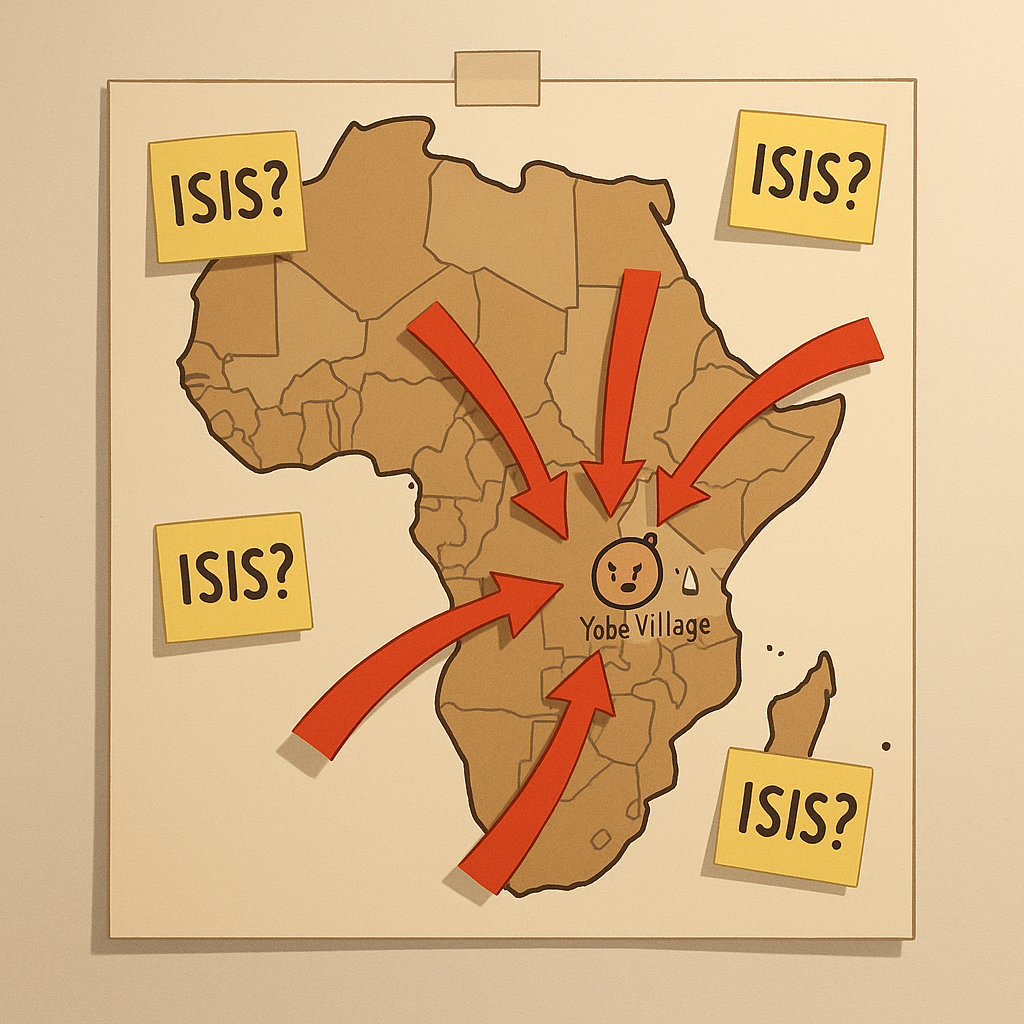

Pressed by reporters on what intelligence specifically indicated an ISIS presence in this Nigerian village, the spokesperson said the operation involved “multi-layered signals intelligence, pattern-of-life analysis, and corroborating information from partners on the ground,” which is Washington-speak for “a drone saw some people standing together and someone in a windowless office in Virginia drew confident circles on a satellite image.”

Meanwhile, Nigerian officials, already juggling internal security challenges from Boko Haram and various armed groups, were not thrilled to wake up to news that their airspace and sovereignty had apparently been treated like the free trial version of a war game. A Nigerian government representative in Abuja, speaking on background, sighed loudly enough to count as a statement.

“To be clear,” the official said, finally composing himself, “we are not aware of any ISIS presence in that area of Yobe State. We would very much appreciate it if the United States would stop discovering terrorists in places where we have only farmers and schoolchildren. If they keep this up, we may start invoicing them for reconstruction—and therapy.”

In Washington, members of Congress performed their usual choreography of concern. One senator on the Armed Services Committee called for a “thorough review of targeting protocols in Nigeria,” which is a phrase loosely translated as: “We will hold a hearing, everyone will look serious, someone will reference 9/11, and then we’ll approve another budget.” Another lawmaker stressed that “America must remain vigilant against ISIS wherever it may hide,” which now apparently includes villages where residents’ biggest daily threat is a shortage of clean water.

The incident in Yobe highlights a recurring pattern of US military activity on the African continent: a mix of secretive operations, flexible definitions of ‘imminent threat,’ and a tragic knack for converting local civilians into inadvertent geopolitical plot devices. While the operation was reportedly tied to broader US counterterrorism efforts, the people actually living in the Nigerian village were, unhelpfully, not informed that they had just been assigned supporting roles in America’s ongoing War on Adjectives (“extremist,” “terrorist,” “affiliated,” “suspected”).

“Every time there is an explosion, some foreign power says it was ‘suspected militants,’” said another resident, standing in front of a damaged building. “We are suspected of nothing except trying to survive. If they want to bomb ISIS, let them at least find ISIS first. We are not hiding them, we are hiding from unemployment.”

US officials, however, defended the overall counterterrorism strategy in Nigeria and across West Africa, insisting that without proactive strikes, ISIS and similar groups could gain a foothold. This logic—hit places where militants might be, in case they might someday be there more—is a kind of preventative wellness for empires, a geopolitical juice cleanse in which villagers in Yobe get to be the kale.

“We cannot allow safe havens to emerge,” said a senior defense official, presumably from inside a very safe haven in Washington. “When our intelligence shows converging indicators of ISIS activity, we have to act.”

Converging indicators, it turns out, may include: men with beards, gatherings near buildings, the existence of roads, and the unforgivable crime of living in a region that has previously appeared in a PowerPoint deck titled “Areas of Concern.” (Reuters, Dec 2025)

For locals in Yobe, the US strike has done what foreign policy consistently does best: create fear and confusion while allegedly pursuing security and clarity. Villagers now navigate their days with a new, unwanted awareness that somewhere in the world, their existence can be reclassified from “civilian” to “collateral” with a single misinterpreted pixel.

“We did not know the United States even knew about our village,” said one teacher, surveying the damage. “Now we know. We wish they would forget again.”

As calls grow for an investigation—by the US, by Nigeria, by anyone who can reliably tell the difference between an ISIS cell and a family compound—diplomats are reportedly hard at work crafting the modern world’s most overused sentence: “We regret any loss of innocent life.” So far, no one has tried the radical experiment of writing, “We made a mistake; here is exactly how it happened; here is how we will stop doing this.” That draft keeps getting lost, possibly due to a targeting error.

For now, Yobe’s residents are left picking up the pieces while officials in Washington and Abuja trade statements, condolences, and euphemisms. The Nigerian government will protest, the US will promise to ‘coordinate more closely,’ and somewhere in a secure facility, another map of Africa will be displayed, ready for the next confident arrow.

Because in the current global order, there is one principle more enduring than borders, treaties, or national sovereignty: if your village is small enough, poor enough, and far enough away, someone else’s politics can—and will—land on it from 30,000 feet.